Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

Taking You To Places You've Never Been

Adventures, places you've unknowingly missed and inspirational photography – it's all here

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken.

— Oscar Wilde.

This is the first post on my new blog. I’m just getting this new blog going, so stay tuned for more. Subscribe below to get notified when I post new updates.

It’s the world’s best known and, these days, its most popular museum. You could tell that by the queue. It snaked, zig-zag fashion, from a tent inside the vast forecourt to outside in the street. There were no special attractions, just the usual broad ranging fascinating stuff. Less than one percent of their hoard is on display which I find a bit selfish. I’ve never understood why some country, like Australia perhaps, doesn’t put up a building and have some of their 99% others on display.

I dwelt on that as I waited patiently. Also, the Standard of Ur was bugging me. I’d seen it over a decade ago but it had been incorrectly labelled so I emailed the museum (as instructed) but no reply was ever forthcoming.

Today I hoped for better luck, bearing in mind that, although less than one percent is ever on show, some top attractions are almost always there.

Somehow I remained calm during the wait, moving slowly along with the hundreds of others. Rain, hail or shine we come to view the treasures therein and there’s a wonderful sense of anticipation as you walk up the stairs through the Ionic columned portals knowing that some of the great treasures of antiquity will soon be before you although most people pass through without realizing that a small but significant percentage of what’s on show are copies.

Beneath the glass dome that sheds light everywhere I opt to head up a staircase bedecked with attractive Roman mosaics on the walls; some even from Ephesus in Turkey where I’ve visited twice because it’s such a wonderful site and had the third largest library of the ancient world.

Then it’s out among the crowd and there are thousands inside, making it difficult to see some of the displays so I opt for the less packed Mesopotamia section where there’s a glazed lion from the throne room of the fabled King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. It’s one of many of his building projects designed to make Babylon one of the most impressive of the ancient world. A museum in Berlin has the complete Ishtar Gate which has its walls lined with these lions which represent Nebuchadnezzar.

Mesopotamia, a Greek name meaning “land between the rivers”, as in Tigris and Euphrates, was at its height between 1500-500 B.C. and has been imagined as an area for the cradle of civilization. More recent discoveries and dating have made all that old hat. One city in Turkey goes back 11,000 years and other ruins have been discovered going back 12,000 years!

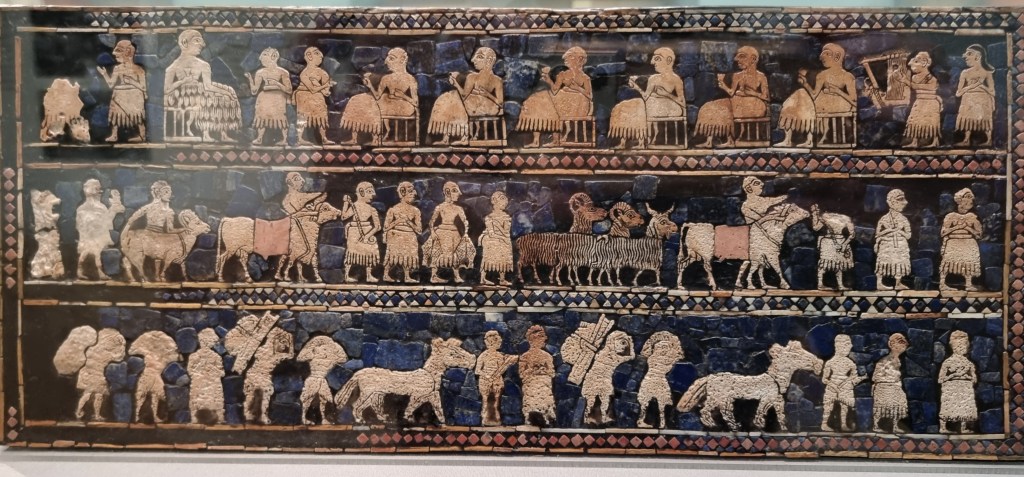

Then, nearby, it’s the Great Death Pit with the Standard of Ur, Ur being one of the great cities of antiquity in southern Iraq. Amongst the treasures within were the bodies of six guards with their weapons and 68 women which came from the Ubaid period, somewhere between 6000-4000 B.C., depending on which site you view. The jewellery and accoutrements of gold and lapis lazuli have been painstakingly restored on a dummy head in an impressive showing of what was available over 6,000 years ago.

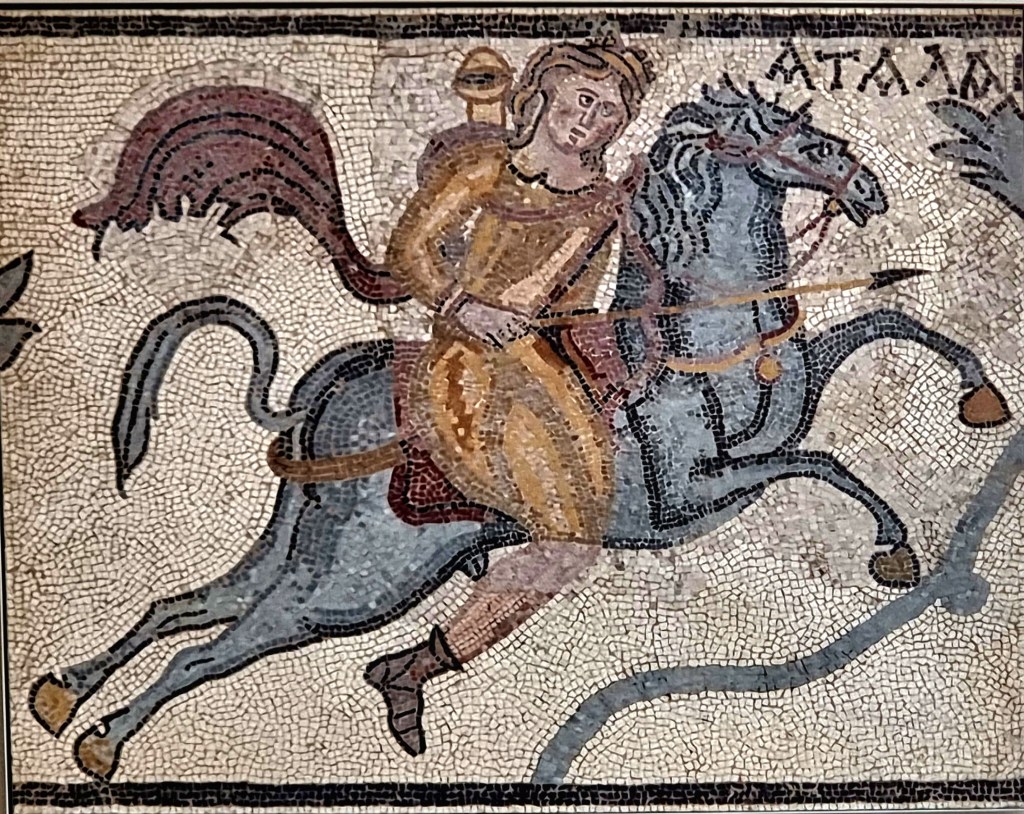

Then, the Standard of Ur, at last, so named because it had been carried on a man’s shoulder like a battle standard but its exact use is unknown. Mosaic scenes done with incised shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli were set in bitumen. War, peace, prosperity and banquet scenes are all depicted in this wonderfully restored treasure that had to be totally redone because the wood it had been set on had basically disintegrated. I finally got to absorb it.

Nearby, Babylonian boundary stones (kudurru) intrigue me. They record the military service of Ritti-Marduk, a chariot commander who now enjoys tax exemptions and is free from legal obligations! Must get one of those.

Speaking of Babylon, is there a more valuable piece than the Cyrus Cylinder? It’s a clay cylindrical shaped work that has the conquest of Babylon by Cyrus in 539 B.C. written on it in cuneiform, clearly extolling his virtues in somewhat narcissistic tones, and was designed to be buried beneath the city walls. It’s the information that it contains, rather than any material wealth or such that gives it pride of place.

Persepolis, 518-339 B.C., in Iran (from the Greek meaning “Persian City”) is another classic place, started by Darius and elaborated on by Xerxes and Artaxerxes before being trashed by Alexander the Great (so-called in English culture) who is not viewed by Turks and others as such because he destroyed so much. The museum contains an amazing cast copy of the Apadana, a monumental columned receiving hall inside the palace showing all manner of people representing states bringing goods and offerings to the rulers.

Next I’m into the famous hoards that periodically seem to get unearthed in Great Britain. Sutton Hoo is the most famed. Dating back to A.D. 600 it appears to have been a royal burial in a 27 metre long ship and, though the boat disintegrated in the acidic soil, a helmet and other goods, too numerous to mention here, survived. They’ve also done a complete recreation of one of the head pieces and it’s noted that a lot of the other goods came from the Byzantine area of the Mediterranean, especially all the silverware. Also, there are no horns on Viking helmets, there never were. However, somewhere on their attire was a belt buckle, a stunning 400 gram work of Frankish design.

The head piece is matched by an amazing Roman bronze face mask visor helmet from the Ribchester Hoard, unearthed in 1796 by a child playing in his father’s backyard. The mere concept of such a thing beggars belief, let alone wearing it! Not recommended in summer.

However, it’s the Hoxne Hoard, only unearthed in 1992, that takes my attention. Over 15,000 silver coins, gold coins and jewellery and lots of silver tableware were carefully extracted after the finder of the hoard, Eric Lawes, notified archeologists and authorities. How did he come to locate the largest hoard ever found? He was looking for a lost hammer of course! He received 1.75 million pounds from the government which he shared with the land owner.

The Thetford Treasure, with its 22 stylish and complex designed finger rings, next competes for my attention. The array of complex Roman designs is wondrous to behold, made even more interesting by the fact they only came to light in 1979.

Nearby I learn about torcs, a decidedly uncomfortable looking necklace that you wouldn’t want to have on for too long. Normally made of precious metals or bronze, just the thought of putting one on has me wincing. Imagine wrapping a 2kg piece of steel cable around your neck and you get the idea. The best one is made of electrum (no, I’d never heard of it either), a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver. These date to approximately 100 B.C. and come from the Snettisham Treasure, some of which was only found in 1990.

Another small bundle of treasure comes from the Isle of Lewis where, in 1839, 78 chessmen and 14 game counters, carved from walrus ivory and whale tooth, were unearthed. You had to be careful carving the tusks as the second dentine, an unsightly substance, was to be avoided. Also, flakes of red paint indicate that black and white was not the original colour here.

In 1959, in a village in Northern Russia, a painting called Black George was discovered being used as a window shutter. It dates back to the 1400’s; amazing it survived! It’s so unusual because St. George is almost always portrayed on a white steed.

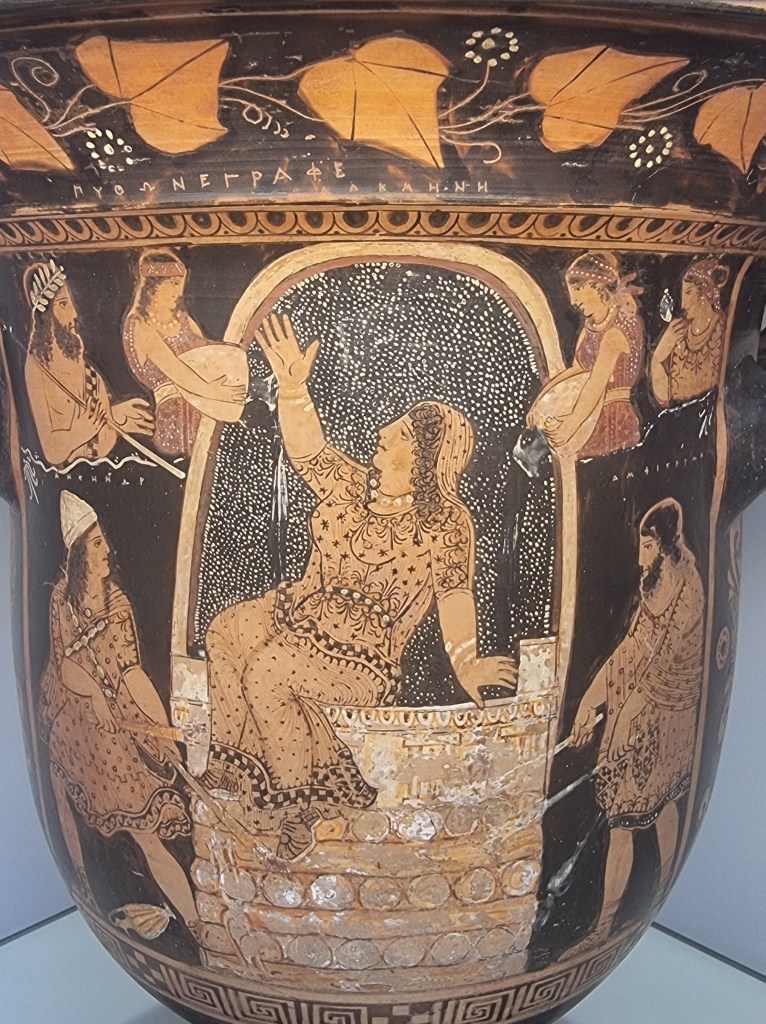

In a section labelled “Greeks in Italy” I come across a bell-krater (wine bowl) that features Alkmena, who I’d never heard of (and neither has spell check), granddaughter of Perseus and Andromeda and married to Amphitryon. Turns out that sex-crazed Zeus, who had it off with just about every female, disguised himself as her husband, made love with her and the result was the Greek hero Heracles. This displeased her husband somewhat and he tried to set her on fire (the part shown in the wine bowl) before she called on Zeus who sent the clouds over to drop some rain on the whole scene.

Apparently there’s a bit of archaeological stuff from a place called Egypt. I mean the sarcophagus inscribed with hieroglyphs (Greek for “sacred words”) was almost as big as the late occupant’s name – Ankhnesneferibre. You’re allowed to take a breath after you pronounce that. She was the last of the princesses installed in Thebes to curb the power of the priests and held sway as the “God’s wife of Amun”. However, all that became irrelevant when the Persians arrived around 500 or so B.C.

Of course, there’s an assortment of painted coffins and the huge statue (what’s left of it) of Rameses II set behind a solid granodiorite stone boat of Queen Mutemwia, wife of Thutmose IV and mother of Amenhotep III . Carved from a single block at Aswan and weighing 20 tonnes, Ramses II was transported over 200 kms to the site where it was installed and it’s just one of many organized by Rameses II, responsible for more colossal statues than any other pharaoh.

In the end, the piece I admired most was the Lycurgus Cup, a truly classic piece of art from the breathtaking Waddesdon collection of the fabulously wealthy Rothschilds. It depicts Lycurgus, king of Thrace, in dire trouble after attacking Dionysus, god of wine (shame on him!), his female followers and Ambrosia the nymph, who then pleaded to Mother Earth to transform her into a vine, which is what’s happening at the moment as Lycurgus is wrapped up and Dionysus, Pan and a satyr torment him. It’s simply exquisite.

On the way out, like them or not, you can’t ignore the human headed winged bulls from the Assyrian Palace of Sargon at Khorsabad, dated before 700 B.C. People tend to gather here as the “in your face” nature of the exhibit makes a good, easy to find, meeting place and it’s an exhibit that you never forget. Bit like the museum really.

It was as benign as it gets; the weather that is. Crisp morning with rising fog from the valley below, a sure sign it was going to be a good day.

My attention turned to the maps of Wingham hinterland. There were hills to be sure, some even had the word Mount before them and I always figure if there’s moisture up there, sooner or later there’s a waterfall somewhere below. Indeed, there was, Potoroo was its name.

The generic common name is adapted from the Eora aboriginal name ‘Poto-Roo’ and was the first macropod to be seen alive in Europe. A pair suffered reverse transportation from the new penal settlement of Sydney to London in 1789, where they were put on display (Claridges et al. 2007). This species was also the first of the Potoroidae family to be formally described by John Kerr in 1792…not that you needed to know that.

The road in was 41 kms, though how much was sealed and how much was dirt I knew not. Google did indicate it would take over an hour, so I surmised that gravel would play some part. No matter, I was off, drink and nibbles beside me on the passenger’s seat.

As expected, it was a somewhat circuitous route. Sometimes you wondered why you were pointing the wrong way and then it would change. Past some rickety old fences, a worn out motorbike atop a bus stop roof and an eye catching metal plate sculpture of two horses. Whoever did that was seriously talented.

Ahead now a mount with stark rocky outcrop took my attention. Was my destination anywhere near that? Three kilometres later the turn-off and dirt road arrived almost simultaneously. Dingo Tops was where I was headed and also the name of the road. From here it was strictly uphill, winding first through farmland and then breaching the outskirts of the forest before twisting through a wonderland of native trees.

At one point scorched trunks bore testimony to the horror of the bushfires a few years previously. Miraculously they had survived, the crown had been spared on this occasion yet, only two kilometres further on, just when I took the first turn off to the falls, they had been devastated by something they were unprepared for – chainsaws!

Somehow, clear felling seems something of an obscenity to me. All nests, hollows and food sources have disappeared, along with the animals that live there. I realise we need wood and that selective logging is much more costly but, just maybe, we need to pay more.

I tried not to dwell on it too much as the final turnoff to Potoroo Falls was indicated. Only 3kms to go but, it’s strictly downhill and 2WD’s are warned not to go when it’s wet. I can confirm the correctness of that sign. It was so vertical they have more than one erosion hump on the route, but the encircling nature is a treasure. Foot ever ready to brake I cruised steadily in the direction of down.

The arrival is somewhat abrupt. Suddenly, half hidden by leaves, there’s a solid toilet on the right and, a few metres further on, a not-so-huge carpark for four vehicles (or five if you’re all friends).

Though it’s school holidays, only two cars are there. Depending on which sign or website you refer to, it’s 900 metres return or 600 metres one way.

I mean, can you believe, NPWS says the following: “From Potoroo Falls picnic area, follow Potoroo Falls walk around 1km upstream along Little Run Creek” yet, below, they say it’s 900 metres return to the falls.

No matter, I’ve got my walking poles and I’m off, initially past the largest recorded watergum, Tristaniopsis laurina, which is nice to know but not overly exciting. I’m waterfall bound and, once upon a time, it involved one minor creek crossing but fallen giants have made sections impassable so now it’s three at least. This is where the poles are indispensable! No wet feet for me.

There’s the usual moss and fungi, those colourful understory occupants that help keep the place alive and the water, unspoiled by humans, is almost invisible it’s so clear. No wonder people want to swim here….except there’s one small problem – it’s very cold! However, I imagine in summertime it would be more bearable but two people give it a go but only get ankle deep before calling it quits.

Which reminds me, I would not recommend this excursion immediately after rain, which is when I usually head for waterfalls. The crossovers with lots of water could be seriously dangerous.

Oh, and the falls themselves? They’re picturesque, as is the whole walk, but you wouldn’t call them spectacular. It’s simply lovely being there, putting your feet up and soaking yourself in the atmosphere, figuratively speaking of course.

Myself and a male parent tried to get to the top of the falls but it was too slippery, too dangerous. Others had died here before, didn’t want to add to the list.

On the return trail you could clearly see where the track used to be and why it was a little rough in places but I couldn’t help but recoil from posts that label it as a 4??? For what it’s worth, in my opinion, it barely rates a 2.

Four is ” Grade 4

Bushwalking experience recommended. Tracks may be long, rough and very steep. Directional signage may be limited.”

The reality is it’s neither steep nor long and, since you’re following the only creek for miles, directions are simple.

On the road home I hoped to see a sign to that mysterious rock mountain but, to this day, I don’t know what it’s called or how to get there. Still, it was one lovely outing.

Funny how things keep surfacing in one’s brain. Won’t let go, refuse to be ignored. So it was with “The Canyon”, so listed but often called the grotto by locals. When I was there with Mr. C we hadn’t pushed right in; Mr. C had never gone past a certain point and, frankly, I couldn’t blame him or anyone. It’s a tad dangerous and decidedly claustrophobic where the roof of the cave is so low you have to double over and shuffle half a shoe length at a time. Still, there was frustration at not having had an attempt and the previous time I’d been, over a decade ago, the photos I’d taken weren’t that good.

Outside on high the wind was raging, gusts of over 70 k.p.h. bent the limbs and scattered loose leaves asunder. It was no day to walk across a ridge as I’d originally intended. Time to head for the canyon once more.

Heath banksia

It was decidedly unpleasant riding the bike to the trailhead, a firm grip on the bars was de rigueur while being buffeted. For once I was glad to get off and start walking, this time from Centennial Glen carpark. Though a little exposed there was enough vegetation and the banksias were prolific. Fern leaved, Heath leaved and Hairpin were three that I recognised but, the gum trees have over 100 varieties up here, so only experts need apply for that identification.

The steps start, though that sentence seems redundant as they always seem to be nearby somewhere in the Blue Mountains. It’s not far down when you come to an exposed lookout and the sheer cliffs and vast horizons are apparent but it’s only momentary as you plunge further and the forest surrounds once more.

Strange rock shapes and cliffs with colourful lichens now become a feature and the bent and twisted white gums at the top become wondrous tall and straight ribbon gums where the winds are absent.

It’s a serious descent now, the last 100 or so steps have hand rails in places, so steep and potentially unsafe would the trail be without them. I’m heading right at the intersection at the bottom. It leads to The Canyon (sometimes referred to as the grotto), a small cavern with waterfall that attracts visitors, especially in summer when the locals sometimes come down for a dip.

A foreign couple who have caught up also want to see it but they don’t really know where to go so they’re looking to me for instructions. At the overhang it’s quite precarious but I’m determined, though you can barely make any progress, so cramped is the space. As described earlier it’s barely a shuffle and so tight my water bottle in my right pocket catches on the rough wall, is dislodged and, shock, horror, gasp, it quickly rolls and falls over the edge into the stream.

Immediately I know it has to be retrieved. Leaving a plastic container in the wilderness is simply not the done thing. I shuffle further along and reach a spot where I think a descent might be possible and carefully survey it. It’s a scary short drop but I make it safely and it has a bonus inasmuch as it gives me a different angle on the waterfall and its vertical log that has been entrenched for a few years now.

Getting back up is more problematic and it takes several minutes to ascend, ever frightened that my shoe might slip on the decidedly moist surface and, with good reason. Luckily I make it without further incident because the other two departed without offering help. Relief is palpable.

Now it’s back up the steep stairs, pausing here and there before I reach the intersection that will take me to Centennial Glen. Heading left takes you to a utopian canyon with towering walls much favoured by rock climbers (there are fixed pitons everywhere). In the middle is a glorious forest of pencil straight ribbon gums and, in a couple of places, water cascades from unseen streams at the cliff top. All the way to the curved, overhanging sandstone ledges that shelter prolific fern growth. As a place to bushwalk, it is without peer.

Above, the rock climbers and abseilers have taken over. Places to clip in are everywhere. People hanging one mistake from death have a taste for adventure that exceeds mine. I tarry awhile watching a pair as one supports at the base while the other chooses climbing routes. It must be exhilarating, though they never stop to take in the view; it’s all about chalk on the hands and finding the next hold.

I move around to the noisiest fall and rejoice in walking behind the cascade and listening to the huge drops flash in the sunlight and splash on the resistant sandstone right beside me. As a pause-for-refreshment stop it’s hard to beat. It’s not often there’s so much noise in one spot in the bush.

It’s turnaround time, foregoing the pleasures of the panoramic views from Fort Rock further up the trail and heading back home, having got what I came for.

Castle Rock

Ignoring the screams beside me; “You’re going the wrong way, turn right, turn right!” Deep inside I believed the direction we were heading was correct as we rolled into Lynton, aiming for a railway…only this is a special railway, so called.

It has two cars that pass each other on their 854ft route of 500ft altitude. Each has a 700 gallon tank that balances the weight of passengers and controls the clamps that serve as brakes. Water is released from the lower unit until it is lighter and thus is pulled down by the higher train. All this is further controlled by water-powered brakes.

All the water comes from the West Lyn River about a mile away and the discharge returns to the river. Can’t get much more environmentally sustainable than that!

And, yes, we were at the right place, as I discovered when I walked into a mechanics bay, not being able to find the local tourist information centre. “Just two streets down and turn right into the carpark”, I was reliably informed.

What was also handy was a café with a large skylight roof, just the ticket for chilly days in England we couldn’t help but think, as we savoured our hot broths before the big descent. Further en route we passed a makeshift van that sold ice creams….especially ones for dogs! Couldn’t help but reflect that they have a status here not enjoyed by the canines of Australia.

Finally, at the railway, so called, you couldn’t help but be entranced by the view down to Lynmouth and the headlands beyond. For some obscure reason, during my research, I thought the railway was the only way down which, not surprisingly, is far from the truth. A walking trail that crosses over the railway is available and a road comes in from the far side.

The distinctly green carriage that seats/stands about a dozen at a pinch is an odd affair. Seems like little has changed in the over 100 years that it’s been running. The brakes, that control the whole system, actually lift the carriage 2mm off the rails, none of which you’re aware of on your journey.

At the bottom Lynmouth, ever seeking to boost its tourist popularity for the last 150 years, seems to have succeeded admirably. With the main street bustling with cafes, tourist shops and the like we stroll in the fair weather beside the river which begat the name. Though the tide is noticeably out and the boats lie stranded, there’s still some water trickling by.

They are not always friendly waters however. In August 1954 the people here suffered the worst flood in English history. 34 died and 100 homes were swept away, like a falling stack of cards, in this unmatched catastrophe which is hard to imagine on a benign day such as this. We tarry awhile at the ice cream parlour and the old stone church, all the time rubber-necking the scenery.

We also spend time on the beach, though not beach as we Aussies know it, no, more your pile of levelled rocks by the seaside riddled with debris like kelp and the crushed shells of a variety of molluscs. There’s also a few lines of mossy posts, whose purpose escapes me unless they were for boats delivering goods at high tide to the adjacent shops, something made redundant when delivery vans found their way here.

We head for the railway again, this time it’s packed both ways and, at the top, we seek directions off the driver to the Valley of Rocks. 15 minutes one way and 40 the other with a 45 degree slope we’re advised. With our aching legs it’s a no brainer so we set off down one of the main roads of Lynton but pause for a cemetery that’s awash, not only with old gravestones, but thousands of white bluebells. We’re later advised that is was mainly a special burial place for nuns.

In time we reach the carpark, the first of three it turns out. Everything is in view but it all seems a long way away, even though it’s probably only a kilometre to what seems to be the main attraction, a jagged rock prominent on a hillside with the sea beyond. It’s only when you nearly reach it that the spectacular view and reason why people come here becomes apparent.

Castle Rock is a stunner, with the turquoise sea way below and a cloud line on the horizon, it has to be one of the best views in all Britain. Add a little gorse for the foreground and there’s your postcard for the trip.

We stop and chat to some walkers. Armed with walking poles they’re obviously more into it than we are and they advise that it’s only half an hour back to the railway head along the cliff path. Lorraine suffers from vertigo somewhat so it was a challenge but she opted to give it a go, bearing in mind neither of us really wanted to walk back along the road. It was fortuitous, because, for Lorraine, it was the best walk she did on the trip.

There’s a gate some way along, just where the forest takes over from the sea, and from here it’s the Poems Walk Coastal Path, which I loved. They have billboards and anyone is welcome to pen something and fasten it to the board. Time didn’t permit to read all of them but I couldn’t help but wish there were more such walks. Someone in Australia get inspired!

We returned with 10 minutes to spare on our four hour parking ticket. Exhausted and exhilarated at the same time, we both knew it had been a more than satisfactory day.

Such was the man’s fame that there’s a hotel in Tenby that still advertises the fact that he got completely sloshed and left the manuscript of what is arguably his most famous work, Under Milk Wood, on the stool. I’m referring to Dylan Thomas and the Coaches and Horses Tavern, in the improbably named Upper Frog Street.

Laugharne Castle

Today however, we’re at his real home town, Laugharne, which you pronounce with the “augh” silent. Here there is Dylan’s boatshed, where you can still buy a cup of tea. Well, when it’s open anyway. Things in this area are much based on seasons so it pays to check beforehand.

THE BOAT SHED

However, the standout in a photographic sense is the unmistakable Laugharne Castle, yet another ruin in another key scenic spot that is long past its use by date. Somehow its jagged walls with some remnant castellations, rising from a large mound by the waterline, are perfect eye candy and dominate the landscape as you’d expect from a true fortress.The

It all happened in Norman times. 1116 was when Robert Courtemain was recorded as trusting its care to Bleddyn ap Cedifor and, in 1171–1172, Henry II of England and Rhys ap Gruffudd agreed on a treaty of peace. When Henry II of England died in 1189 the castle, along with others, were seized by Rhys ap Gruffudd of Deheubarth in the same year. The castle may have been burnt at that time. It was rebuilt by the Normans and, in 1215, was captured by Llywelyn the Great in his campaign across South Wales. By 1247 Laugharne was granted to the De Brian family but, just ten years later, Guy de Brian was captured at Laugharne Castle by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd and the castle destroyed.

Flanked by vines, shrubbery, the occasional tree with the lush green sea grass of the tidal flats of Carmarthen Bay behind, it stands stark against the sombre background of indecisive clouds. Will it rain or nay? That is the ever present question for viewers of this area.

The path, frequented by Dylan on his way home from his favourite Browns Hotel, crosses the Taf, a twisting feeble excuse for a river but made lovely by an historic stone bridge. It’s all linked to the Coastal Walk of Wales and leads up towards Dylan Thomas’ garage, where much of his stuff was penned and where splendid views of the fluent Carmarthen Bay can be had as far as the eye can see.

The Writing Shed

Passing by I could help not but pause and find inspiration by merely being here, understanding the rhythms of nature from this viewpoint and spying his desk and chair, still there after all those decades. Oh, that I had a key to unlock that door, a pen and paper to scribble upon and an hour to spare.

A blackbird seems to mock me walking by, hopping from branch to branch as if to get a better angle, eyeing me for what reason I know not. Dylan’s grave is on a narrow forest trail further up but we choose not to go because you are advised that it’s muddy and a slip and fall on a murky path is not what we need or seek. His famed boatshed is reached but it’s closed, as we’ve come to expect of many attractions, even though it’s spring and many are the walkers who would love a brief repast in this place.

On the return, furtive glances across Carmarthen are obligatory. It’s the sort of place you literally don’t want to leave, but beckoning time is our master so we stroll back to what turns out to be a simply gorgeous tea room called the Owl and the Pussycat. Inside are cross stitch works of the highest quality, quirky notices and a lady who’s heard it all before and will stop you with cutting, though often humorous, remarks, reflecting her salty individuality.

The town has become more popular in recent times because a T.V. series called “Keeping Faith” was filmed here. Thus the modern tourist is surreptitiously drawn in to history of today’s times, but hopefully getting some rub off from yesteryear while they’re here. Surely they walk beneath milk woods still and ponder Dylan’s verse, “We are not wholly bad or good, who live our lives under milk wood.” Laugharne – I loved it!

DOWN IN THE BLUEGUM FOREST

Walk in the Blue Mountains often enough and there’s a name that will crop up. Blue Gum Forest. No serious walker can avoid it, so the fact that I’d managed to not go there for 76 years indicates how serious I’d been. For the seasoned hiker it’s usually part of a multi-day walk involving backpacks and sleeping out, something I’d also managed to avoid. Still, I was aware of it and a small part of me always wanted to see it.

Plus, the place has history. Could it have been coincidental then that I picked up a local paper and there was an article about Myles Dunphy. For those of you unfamiliar with the name, his passion for nature was such that he carries the title, “The Father of Conservation”.

Born in 1891, the eldest of seven children, his escape was the bush. The wilderness renewed his spirit, as it does for all those who indulge. That’s what communing with nature can do for you. In the year of the outbreak of World War 1 he formed a walking club in Katoomba; 12 years later he married and, in 1927, he was a foundation member of the Sydney Bush Walkers Club. It’s then that the term “bush walker” was coined.

For the rest of his life he fought for the protection of natural areas, purchasing the lease on the land that contains the Blue Gum Forest in 1931 for 131 pounds with help from his friends; lobbying government and newspapers continually, mapping areas for conservation, aided by others and, eventually, the government finally allocated 156,676 acres for a national park in 1957, just one quarter of what the group wanted, but luckily it has since been expanded to the hoped for size and is today’s reality.

Miles Dunphy Reserve, Oatley

A few years ago I walked in Myles Dunphy Reserve in the little known Sydney suburb of Oatley. Somehow it evoked passion in me that nothing more major had ever been done for this icon of Australian conservation and his compatriots who have had far more impact on Australian society than others who got more publicity for much less. The tens of thousands of tourists that flock regularly to the areas of the Blue Mountains should be more aware of just how fortunate they are to have had people of his ilk.

VIEW FROM PERRYS LOOKDOWN

So it was, as I gazed down from Perry’s Lookdown, named after the deputy surveyor general under Mitchell (or maybe an innkeeper), that thoughts of the Blue Gum Forest came to the fore. It wasn’t that far away, surely; in fact it was right below me. Maybe I’d have a go. My house sit at Blackheath was for a fortnight, time was not an issue.

WIND ERODED CAVE

Just a few kilometres back at the Wind Eroded Cave I came upon a serious hiker, replete with overnight backpack. He could answer my questions as I probed the difficulty of the stairway below Perry’s. He said it was about three times further that the Golden Staircase. I’d done that a few decades earlier, in the cold of winter, and remembered being stripped down to my singlet and sweating profusely when I reached the top. Now, with dodgy knees and deep into old age, perhaps I shouldn’t go.

Resigned to not going, I nevertheless queried a lady at the Blackheath NPWS office a few days later. She was optimistic. “If you take your time and it’s not steps all the way.” I decided right then and there it was time to get some walking poles, something I’d been considering for a couple of years. She showed me some but suggested I go into Katoomba and check out the outdoors stores for some that were more economical. Since the cheapest I was looking at here were comfortably over $200, I thought that was a good idea.

WALKING POLES AT LAST

At the Summit shop in Katoomba I came across a pair for only $69; that was more like it. Then, one of the assistants said “The Blue Gum Forest is beautiful at the moment”. Suddenly it became a commitment and I walked out with the poles, trying them out successfully the next day at Colliers Causeway.

The day after that it went pear shaped. “Walking” the dog I was house sitting for, mounted on my bike, I managed to snap the chain. It was my means of access to the trail head.

There’s a bike man at Blackheath (by appointment only); there’s one at Katoomba (shop has closed); the only option was Wentworth. Braving a mass of holiday traffic I called in, was told everything in the drive chain (cluster, sprockets, chain) needed replacing, but they put a new link in to get me out of trouble. The bike worked fine.

The next day was perfect, clouds were in absentia, a decision was made. Down the 9 kms to Perry’s Lookdown, remembering food, drink and walking poles. It was time to pay homage to Mr. Dunphy.

GOING DOWN – AREA OF THE TWO FOOT STEPS

If there’s two things that get a mention from any walkers who’ve done the trek, it’s “The two foot steps” and, “it’s not all steps”.

I left the bike at Perrys, no need to lock it up, only bushwalkers come here.

You don’t have to wait for steps, they start immediately. Just how many are not recorded, but everyone says there are lots of them and we’re talking four figures. I pass Perrys and Dockers Lookout, where the trail momentarily diverts inland to cross over the tiniest of creeks before swinging back to the dramatic descent through the cliffs. Here the “two foot steps” became a reality. I dreaded the thought of an ascent through here. The trail was old, steps were worn and narrow and stretching my painful knees any further than necessary wasn’t something I was enjoying.

NOT THE EASIEST OF TRAILS

Confidence was also at a bit of a shortage and I blessed my decision to buy the poles. Having something to lean on in tricky bits was a godsend. At times it was so steep the trail all but disappeared, at another spot it vanished into the forest.

In time I got beneath the cliffs and moved into the forest; though soil was a bit thinner here on the slopes so the growth isn’t as prolific, though I did catch sight of one spiky sprig of wallum heath with a sprig of white flowers.

THE SPRIG OF WALLUM HEATH

I’d been at it for over an hour, this listed 2 km trail, and not a sign of “the flat bits”. Further down I came upon the tremendous job that NPWS are doing in putting in same size log steps. The work must be so time consuming and is only achieved by utilizing helicopters to drop equipment in.

FLAT BITS AT LAST

At last, some flat bits. They provide minimal respite and I’m seriously worried about how long it will take me to ascend. The descent is the toughest I can ever recall. I’m certain by now that the descent is further than 2 kms. It has to be said that the popular websites are universally erroneous. They’ve all said 2 kms, even the NPWS.

A lady runner who’d passed me earlier was on her way back. I queried how long the descent had taken her. “36 minutes” was the reply. I’d almost hit the two hour mark.

I’m aiming for a large stand of Eucalyptus deanei trees on the junction of the Grose River and Govetts Creek and I finally reach a T-intersection where I can turn 600 metres to the Acacia Camp Ground, a popular haunt for overnighters. At around 200 metres there’s a side trail. It leads to the river which can clearly be heard.

It’s sublime; the forest reflected in the upstream pondage, rapids deflecting the flow in front of you and more drama leading to the distant dominant cliffs beyond. I capture the scenes and head to Acacia. Here, the sound of a banjo wafts through the still air. Amazing, someone has brought an instrument here, I must shoot the source.

There’s a trio of small tents not far away and I head for them, only to discover that the banjo is merely recorded music playing through a speaker. Yet, somehow, it’s so right here. It belongs to three Asian youths and I fall into conversation. Miles Dunphy is unknown to them so I explain that, without him and his ilk, camping may not have been possible here. Such is the modern world that the phone comes out and they’re typing his name in immediately. Somehow, I feel I’ve done something for Miles but, in truth, I’m probably only serving my ego. Still, it feels good to know that his legend will live on through the next generation.

It’s time to return. At the intersection, where the sign says “2 kms”, I set my app to check the accuracy. Now it’s up all the way. First the occasional flat section. I haven’t quite cleared it when the one kilometre notification is sounded.

The steps are relentless but I’m making reasonable progress. I catch and pass a family who’d overtaken me on the way down. They can’t believe the progress I’m making. That’s okay, I can’t either.

Two kilometres passes by and it’s still a long way to the top. I’m back in the land of the two foot steps but still making progress. Every so often there’s a pause for refreshment. Three kilometres is signalled as I near the plateau and it’s 3.24 when I get to the bike. It’s taken me around 1 ½ hours, about half an hour less than the descent. I had been passed multiple times going down but by no-one on the up, surely a reflection of the state of my knees and, strangely, I felt good, even though the ascent was over 2,000 feet.

The poles had been a significant aid and I rode the 8 kms back in a satisfied manner until the last small incline. It was there it hit me. I could barely turn the pedals. Maybe it had all been adrenaline after all.

The view from Lamberts Lookout

Lunch was a gourmet pie for both of us. There was little initial discourse because we were so hungry. We’d started out around 10.15 to do a listed 5.2 kms walk. How hard could that be with only 281 metres in height variation? We’d both done bits of the trail before, just not the way we were doing a full loop today.

It was now 3.10, as in the p.m.; how had we so badly underestimated the time factor? Four and a half hours, average just over one kilometre per hour, what had happened?

Since we were both into photography, that got the initial blame but, for me, in truth, the trail was so time consuming because of the variation in surface. Revisiting the internet site we’d used for guidance showed that they claimed to have taken 2 hours 20 minutes with 281 metres gained; they were young and even they complained about the roughness of the trail. They also hadn’t attained 70 years, not even when you combined their ages, something we couldn’t claim.

Later checking of another site said to allow 3 ½ hours, with a 473 metre height variation, which better reflected our experience. Just goes to show not to believe even the most visited site on the internet. Yet another site listed the distance as 6.2 kms.

It’s all downhill from here

The crux is that Porters Pass, Colliers Causeway and the Overcliff Track are not part of the NPWS area of Blackheath. I’d like to say it’s council cared for, but that would be so erroneous. It may be under the council’s control but, other than some signage, they obviously don’t have it on their priority list. They probably figure that there’s little benefit for locals, thus the trail is in appalling condition in parts, unaided by the heavy rains in recent years. Rutted, rocky and decidedly uneven, it demands constant footfall attention.

Panorama of the cliff you have to walk below

Yet this walk is one of the most scenic and has more variety than any other I can think of in the whole Blue Mountains. Many internet sites rate it THE top walk. There’s waterfalls, giant cliffs, panoramic views, canyons, ragged rocky outcrops covered in colourful lichen and a variety of flora and fauna. It’s also a mecca for rock climbers, whose grunts and efforts echo eerily across canyon walls. They’re so prolific they even have pitons permanently fastened on many of the rock faces.

In the beginning at Porters Pass

We’d started out from Burton Road, where there’s no real carpark, just a couple of spots at the end of the street. Me and Mr. C, whose name is also Ian Smith but I’ve chosen to identify him by his middle initial. We’d met a few years previously on a misty drizzly day on the eastern side of the Blue Mountains. We’d fortuitously bumped into each other on the trail, the only two people out that day and we’d met; what were the odds we both had the same name?

Since then we’d done a couple of walks together and kept in touch via the internet. We’d explored new territory, nearly been landed on by some base jumpers and had seen a trio of waterfalls at their best.

Mr. C showing the way at Porters Pass

Today was windy, chilly and overcast, the latter making it better for photography; with even light making for less contrast. Initially there’s not much to see, but you soon come to Lamberts Lookout. Here I appreciated the fact I’d brought both a jumper and a parka, not to mention a beanie, as we gazed out beyond a nearby sandstone cliff across to Kanimbla Valley and got blasted by the wind. It’s just a warm-up, pardon the pun.

Next it’s all downhill, winding your way to the base of the massive cliff face on uneven steps and turning left onto Colliers Causeway, constructed in 1916 on top of a talus slope and named after Henry Justice Collier – a Blackheath store owner, one of the first trustees of the Blackheath Reserves and Mayor of the Blackheath Council (1922-23).

The cliff is oppressive as it towers over you

I was so glad I’d purchased my first ever walking poles only the day before; they proved to be more beneficial than I could have dared hoped for. Continually falling behind due to photographic opportunities, I needed them to hasten the chase.

It’s not an easy track

The dominance of the cliffs cannot be understated; places where massive slabs have sheared off can be clearly seen as you gaze skywards. The trail along Colliers Causeway undulates continually, the footing isn’t always secure but we’re making progress and the scenery is breathtaking.

Slippery by name, slippery by nature

The next variation in scenery, after about a kilometre (seems further), is Slippery Slide Falls. You can hear it before you get there and I know I don’t need to worry about catching up to Mr. C because waterfalls, or streaky photos of same, are his dream time and he’ll blow lots of time getting the right image.

There’s a track there somewhere

One of the most dramatic bits of walking in the whole Blue Mountains, you have to rock hop a stream, find a way through large moss-covered boulders and then mercifully grab a hand rail to launch yourself upwards on the narrowest of staircases cut into the rock face with the slimy brown cascade beside you. Those with vertiginous problems need not apply!

The Canyon aka The Grotto

Up you go to an intersection where a short diversion takes you into a small canyon, aptly titled The Grotto, featuring a low overhang with a picturesque waterfall and pool, a favourite for locals in summer. Then it’s back on trail and heading upwards to Centennial Glen, replete with old growth eucalypts standing tall, memorable overhangs with lush fern clusters, a walk behind a couple of waterfalls and the echoing sound of those climbers/abseilers.

Centennial Glen

It’s all a bit surreal but then, after another sharp climb, you’re suddenly on top of the plateau and everything changes. You’ve reached Fort Rock, welcome to banksia land, low scrub and 360 degree panoramas. Up here the trail is not as well trod and you occasionally query if you’re heading in the right direction, except there is no other way to go.

Mr. C checking on how to get out while I shoot from Fort Rock

Reaching a clump of weather battered exposed white gums is a sign you’re getting close to the end, which is good, because Mr. C’s strength is not in going uphill these days. We meet a man walking his pet greyhound whose name is Jamie. Over the next quarter of an hour he walks with us, invites us for coffee (politely declined) and, after pointing out his house, almost obscured by the forest, tells us to “Drop around anytime”. I reflect that these are the kind of people you meet bushwalking; chatty, friendly and willing to share.

Into the gum trees

Finally we’re at the final intersection and it’s just five minutes back to the car or, more importantly, less than ten minutes to a gourmet pie, which is where we came in.

I’d done nothing much in the morning, couldn’t think what to do with the afternoon. Then it clicked, there’s street art you haven’t seen yet. Previously, I’d stumbled across them while house sitting at Eveleigh. Hundreds even. This time I decided to look them up first.

That’s when I found Scott Marsh. Well, actually, I’d already found him before; I just didn’t know it at the time. Randomly wandering the streets of inner Sydney suburbs I’d stumbled across a couple of his legendary pieces. The political ones. The ones that excite interest, like Tony Abbott beside Tony Abbott in a wedding dress on his unique imagined wedding day. I loved it.

However, Scott is seriously talented, having been a finalist in both the Moran Art Prize and the Archibald. He’s come a long way since tagging Sydney trains when he was twelve. He’s one of many who haunt the back alleys of suburbs like Newtown (especially Newtown), Marrickville, Erskineville and Enmore. Much more quality than you’ll see at the Contemporary Gallery at Circular Quay.

He also painted a Kanye loves Kanye mural which was complained about and he claims he was paid $100,000 to obliterate it. Hmmm, who knows?

I wrote down a couple of other possibilities as well, but was pleased I’d already viewed half of the works previously.

THE BIN CHICKENS

The goal was an obscure lane called Teggs at Chippendale this time. The ibis, aka rubbish renegades, trash turkey or smelly flamingos. Here they were splattered all over the side of a pub wall. Only problem I had was getting there. You see, that’s one of the things about street art, some are in obscure locations totally unsuited to vehicular traffic. That’s where the pushie comes in handy.

THE THE RIGHT OF THE BIN CHICKENS

Somehow, Miss Direction decides that part of the best way to get there is to travel 4 kms along Parramatta Road. On a pushie??? Excuse me. I drift along the pavement and duck into a couple of back streets to avoid that insanity.

CLEANING UP

Teggs is a narrow way but the wall space is large and littered with Scott’s handiwork. It doesn’t disappoint. I cop a bonus with an employee cleaning the glass doorway then it’s time to head over Newtown way, sort of. Somehow I find myself in the outskirts of Redfern, then through Eveleigh, Marrickville and who knows where, riding through streets I had come to know just 12 months ago.

DOC MARTENS AND MY BIKE

Eventually I wind into Church Street where there’s a Doc Marten mural one side and an unnamed work on the pub opposite by Fintan Magee and Numskull which features two females at extreme ends of and old style communication device of two tin cans joined by a piece of string.

HELLO, ANYONE THERE?

Not far away in Lennox Street there’s an IGA carpark. It’s a treasure trove of works and my favourite is Perfect Match by Alex Lahors but The Ox King and The Emperors Daughter will also command your attention, and that’s just a couple of them.

PERFECT MATCH

In every second back street around Newtown you’ll find works, but it’s important to remember that street art is a fluid situation. What you saw last time may be replaced with a new work or simply painted over.

A HOWL-ER OF AN IMAGE

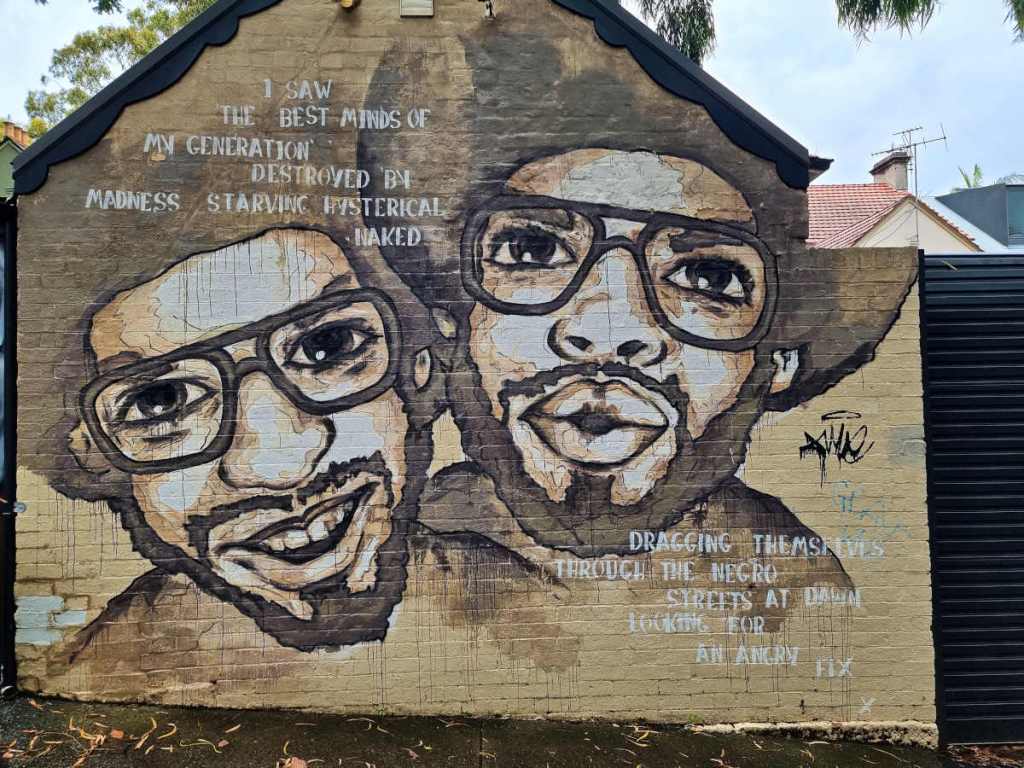

My favourites are the political ones, such as the painting of two blacks by Helen Proctor in Lennox Street with the script “I SAW THE BEST MINDS OF MY GENERATION DESTROYED BY MADNESS, STARVING HYSTERICAL NAKED, DRAGGING THEMSELVES THROUGH THE NEGRO STREETS AT DAWN LOOKING FOR AN ANGRY FIX”, an extract from the famous poem “Howl” written by the noted poet Allen Ginsberg, who vigorously opposed capitalism and conformity in the U.S.A.

Somewhere on Holt Street I view the whale with skeleton and decide to head home. By the time I get back I’ll have spent around 4 hours exploring. It’s enough for one day.

BAD MAGPIES ART IS EVERYWHERE

ONE OF MY FAVOURITES IN AN OBSCURE BACK STREET

Art IS civilization. It’s a measure of how advanced or not society has become. Thus, when I see a new gallery opening up I should be pleased. I’m not.

Not all the art at Circular Quay is bad

How many millions were spent on the new North Wing of the N.S.W. Art Gallery and how much was allocated to refurbish and reassign the Contemporary Gallery at Circular Quay I have no idea, but I can’t help but wonder out loud if either attract many regular visitors, other than for their cafes. I’ve long held a personal belief that if the art work needs explaining (other than its historical antecedents) then, is it worth showing? This is emphasised when you go to many regional galleries and see superb works (in my opinion) yet they never get a gig in the city.

N.S.W. Library (once called Mitchell)

So, today I chose to head for the N.S.W. Library, nee Mitchell, that once was a place where you went to view rare and historical volumes in a huge room overlooked by a walkway and a terrace that holds even more works. These days, there’s more.

The first time I became aware of “more” was when I went to view the Annual Press Photographers Awards. Can’t remember how many times I said “wow” but it was an impressive show.

A terrorist incident in Nairobi from the press exhibition

However, scattered around the library area are many rooms, areas that were underutilised in the past but, these days, are awash with things of interest, and one of those is their historical art gallery, where works, mainly from the 19th century, have been unearthed from storage and now have the best laid out art space in Sydney.

In the middle of each room there are touch screens that give forth lots of information on each item and, what interesting stories there are. There are over 300 on display but they are just the veritable tip of the iceberg of the collection. Here you’ll find classic well known artists like Tom Roberts, Eugene Von Gerard, Frederick McCubbin, Hans Heysen, Arthur Streeton and a host of others as well as many little known.

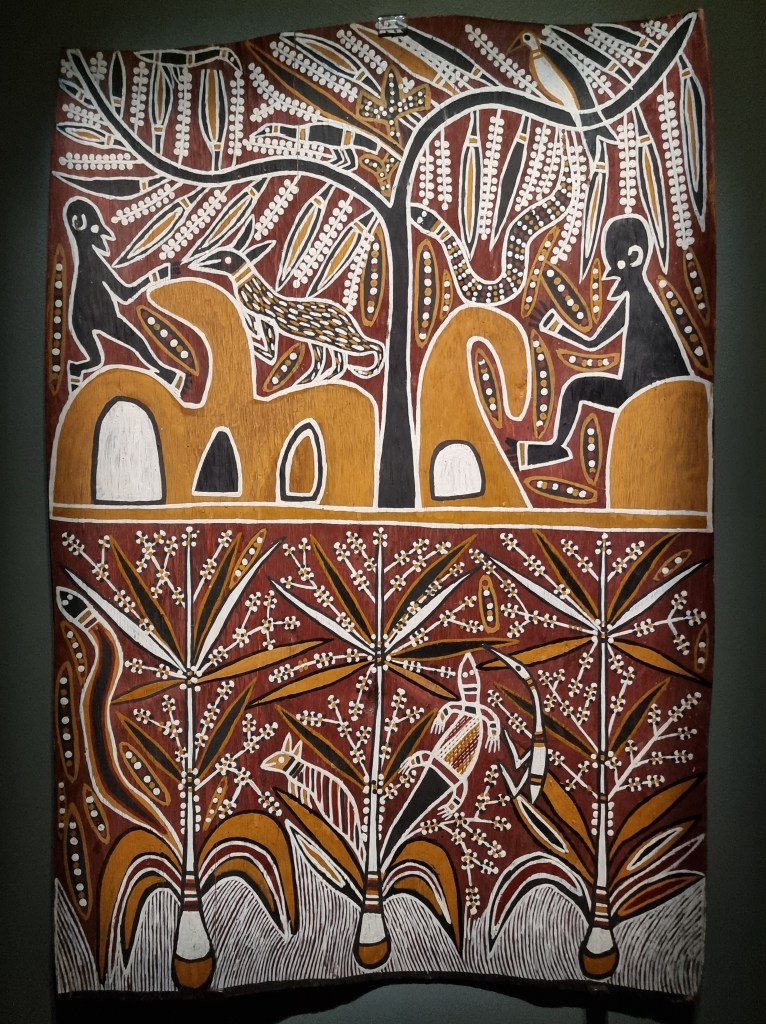

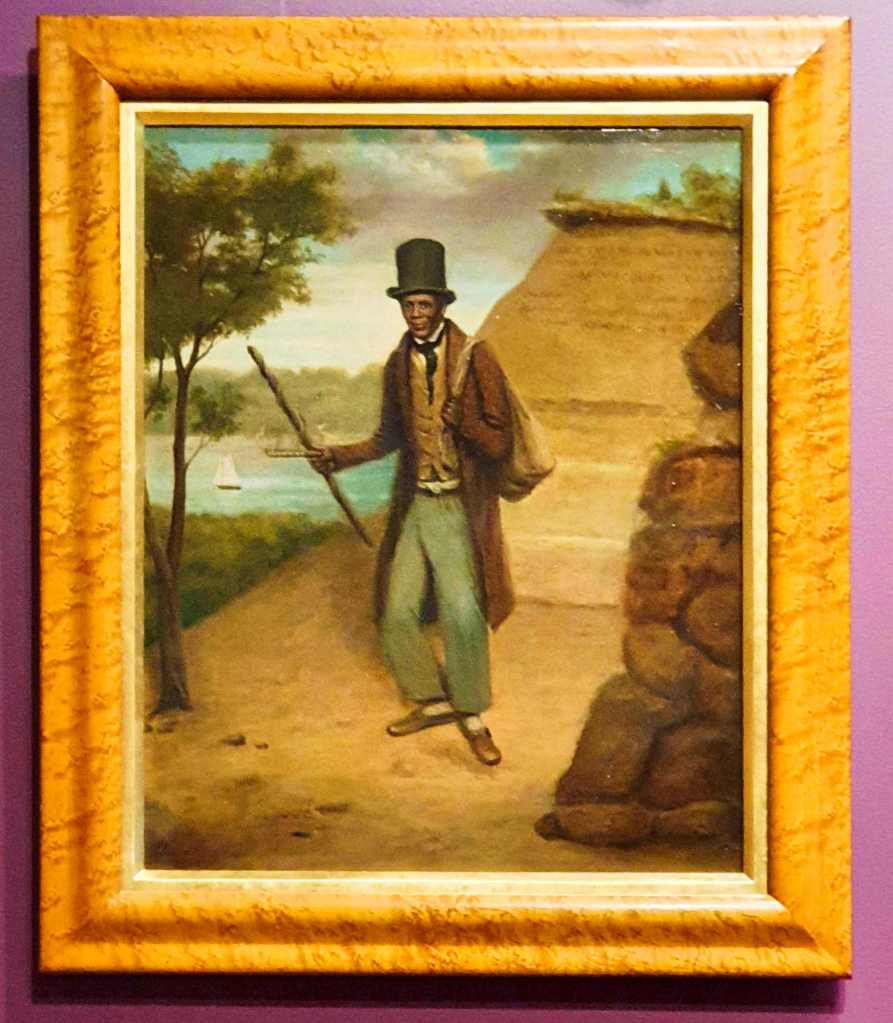

Billy Blue in his finery

Personalities long gone and all but forgotten are here for all to see. I’m intrigued by many. Billy Blue, a convict believed to originally be from Jamaica, was enterprising after his release as he started a successful ferry service from Lavender Bay to Dawes Point. His dapper attire makes his portrait a standout. The portrait of stern faced Sarah Cobcroft, that can’t help but grab your attention as you walk by, followed her convict husband out here and successfully settled in the Hawkesbury area, becoming the local midwife.

Ferry Lane, circa 1901

In 1900 there was an outbreak of bubonic plague in Sydney and the area cited as the centre of the outbreak was listed for demolition. An art teacher, Julian Ashton, secured a grant of 250 pounds and he coerced a group of his students to record the area. An exhibition, of 145 artworks by Julian and 37 students, was later held in 1902.

Janssen’s view of Sydney Harbour

The much travelled Prussian artist named Janssen painted an idyllic, but realistic, scene from today’s Vaucluse area that differs from the British painters’ pastoral bent, highlighted by the two ruffians, apparently consuming alcohol, in the left hand corner

Von Guerard’s landscape

A classic Von Guerard, showing the forest at the confluence of Brandy and Water Creek, with Mount Kembla in the left background, leaves me lamenting the fact that all that bush has since been knocked down.

Bounty Bay, one of my favourites

Beechey’s “Landing at Bounty Bay”, circa 1825, leaves us an historical record of where the Bounty mutineers ended up on the Pitcairn Islands and why it’s so hard to get to the place. The rough treacherous seas are also tragically reminiscent of how the replica, constructed for the famous 1962 movie, also met its end 50 years later in a hurricane off the North Carolina coast when the skipper foolishly decided to head to sea with the false words “A ship is always safer at sea than at port”.

Sophia O’Brien

There’s a fetching portrait of young Sophia O’Brien that also catches my eye but then the mood saddens when you learn it was done six months after she died.

The convex mirror

The Convex Mirror painting by George Washington Lambert is indeed a work of clever art and the U.S.A. soldiers’ camp during WWII at Sydney University brought to my attention something I knew nothing of.

There’s so much of interest here that I know every time I’ve gone back there’s still something different I’ll come across. Perhaps I might see you there sometime…….oh, and they also have a nice café as well!

Stained glass from The Seven Ages of Man in another part of the library

I could hardly forget. I’d sat there on the step of the motorhome shaking my head from side to side and started picking. In the end there were 23. I counted them to keep myself amused, but there’s little amusement in leeches. Rubbery figures sucking your blood and leaving an anaesthetized hole for the blood to keep running through is not a subject that comes up much at dinner tables. At the time it was a personal record (later vastly exceeded in Queensland).

Still, knowledge had made me less wary of these slimy creatures, and, as I applied the wondrous Vaseline around the top of my socks I was able to look forward to the 5.2 kilometre return walk to the base of the 40 metre high Rawson Falls. It traverses three or four different types of rainforest, this remnant from before white man came and stuffed the rest of it up, though even here wasn’t spared entirely. The woodcutters saw to that.

Because the walk isn’t that popular for a number of reasons, you can usually have it almost to yourself. Lack of publicity, distance from the beach attractions at Port Macquarie and the fact that you actually have to get out of your car to soak it all up (sometimes literally) means it’s as close to pristine as you could hope to find

There was a car there already today as I set out past the ideally placed toilet block and into the subtropical rainforest, the first of three types of forest the route traverses. I love the mottled bark of the carabeen and white aspen, so artistic and no two the same. The fluted root system of the carabeen is sometimes mistaken for a strangler fig but, apart from the supports, there’s little they have in common.

The upper slopes are gentle and, as I brush past a large turpentine, I’m grateful some of the giants have recovered though there’s one I have to negotiate, fortunately with steps cut into it, that has collapsed in the recent past, probably due to the persistent rain loosening the soil. The first time I ever walked here, a few decades ago, the memory that lingers was of a large area where the sun was able to come through and birds nest and jungle brake ferns were in such profusion, the like of which I’ve never seen before or since.

There are brush box trees here that may be a thousand years old. From the family myrtaceae, related to eucalypts, you can’t exactly tell their age. Many people are unaware that most Australian trees are hard to date because they don’t have rings, unlike those where it snows.

Leaves crunch beneath my feet as the progress becomes ever steeper, requiring the trail to zig-zag down towards the first lookout. The second time I came by on this trail it was after some seriously heavy rains and the trail was impassable at this point because a minor pondage on the ridge above had flooded over and taken heaps of soil and rock with it. I momentarily put my foot in the morass and found myself in trouble because it was as quicksand and I was immediately up to my knees.

Boorganna was the second ever gazetted public reserve (1904), all 74 hectares of it, and this has allowed the vegetation plenty of time to regenerate, especially timber like the brushbox and cedar that were much sought after.

It’s so diverse that four types of forest are on show here, subtropical, warm temperate, gully rainforest and wet and dry sclerophyll forest. These days the reserve has been expanded to 396 hectares in recognition of its long term value.

At over half way you come to the platform lookout with views to the falls. After that it gets a tad steeper and the forest changes again.

There’s over 80 bird species here, including a rose robin who cheekily lands just an arm’s length away. I curse after the camera refuses to focus and the bird has flown but now I’m at the base of the falls and that spectacle has taken over my attention. Once when I was here the water was so voluminous that a constant mist was drifting by even though I was 50 metres away.

Rawson Falls are virtually unknown because their nearby cousin, the famous Ellenborough Falls, garner all the attention yet, within a 20 kilometre radius, there are many dramatic drops, including one that I was so fortunate to visit once that used to supply hydroelectric power to Comboyne.

Then it’s time to leave and I’m climbing back to the black booyongs, rosewoods and prized native tamarinds further up and rubbernecking a vine that has climbed to the sky on its host while stepping over the occasional tree root. There’s a pleasantness about walking here, deep in the forest yet not having to hack your way through underbrush, simply admire the giants around you.

It is a relief as the terrain levels out somewhat and you know the small carpark is nigh though, in some way, you’re disappointed to be leaving this wooded wonderland that’s given you such pleasure. Never mind, there’ll be another day.